A Memoir

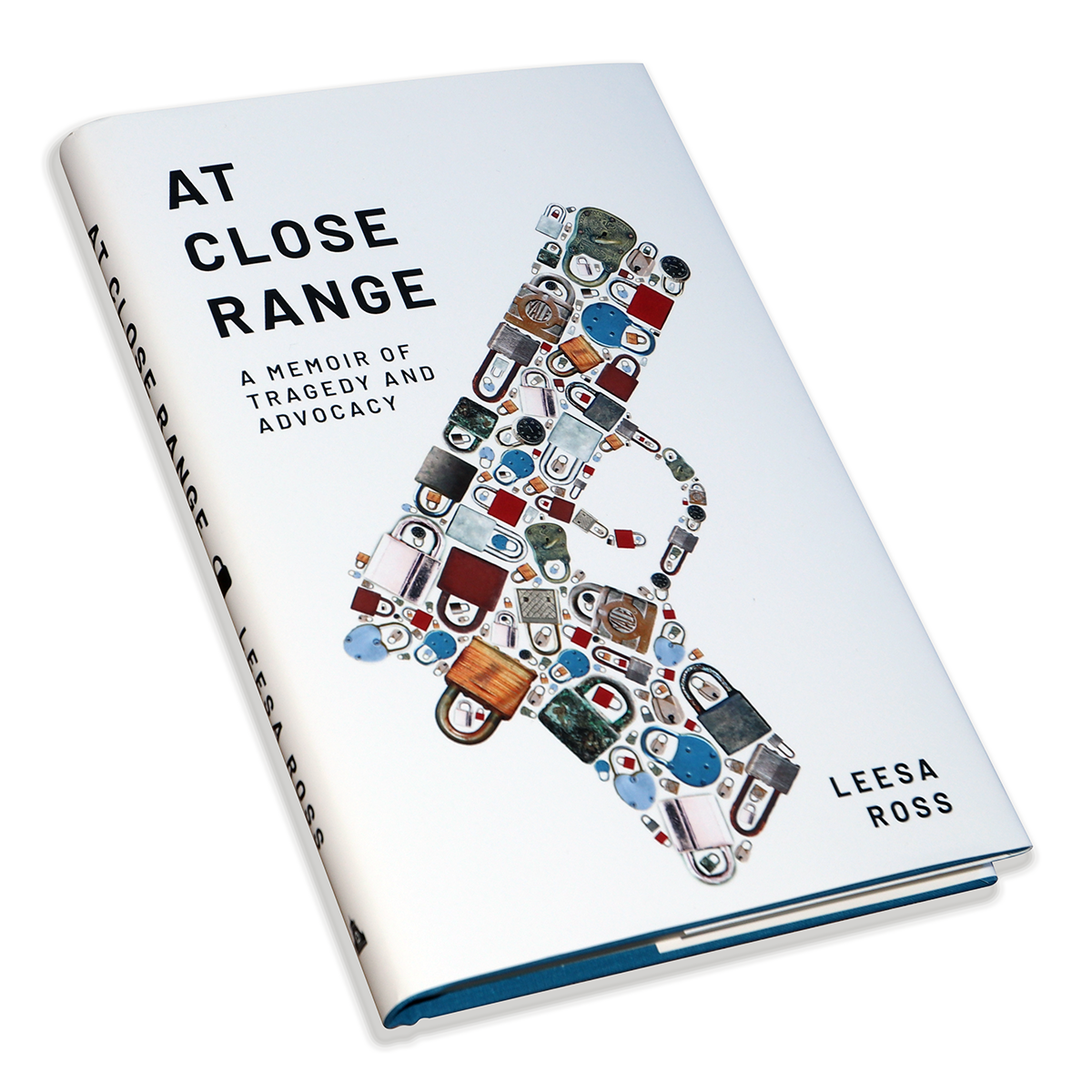

In At Close Range, Leesa Ross tells the story of what happened after her son Jon died in a freak gun accident at a party. Ross unsparingly shares the complexities of grief as it ripples through the generations of her family, then chronicles how the loss of Jon has sparked a new life for her as a prominent advocate for gun safety.

Before the accident, Ross never had a motivation to consider the role that guns played in her life. In the book, she revisits ways in which guns became a part of everyday life for her three sons and their friends. Ross’s attitude toward guns is thorny. She has collectors and hunters in her family. To balance her advocacy, she joined both Moms Demand Action and the NRA.

At Close Range shows one mother’s effort to create meaning from tragedy and find a universally reasonable position and focal point: gun safety and responsible ownership.

All proceeds from book sales are donated to the Lock Arms for Life foundation.

At Close Range shows one mother’s effort to create meaning from tragedy and find a universally reasonable position and focal point: gun safety and responsible ownership.

Preface

There are talks for many things when we are raising our children: sex, drunk driving, and the hundreds of other issues involved with growing up and taking responsibility. We also need a talk about guns–and not the one you think.

It’s not a matter of gun control that put that handgun in the room where my son died, or countless other rooms where people have died. Not enough of us are thinking of the responsibility that handgun ownership should demand. Handguns are weapons designed to kill. There was no effort in North Carolina, where Jon died, to make them safer by instructing those college kids how to live in a world with weapons everywhere.

If the penalty for unsafe gun ownership falls outside of our laws, what do we learn about safety? Drunk driving is an offense even if no fatality results. Unsafe gun ownership can be treated similarly, if we have the courage and love to make it as important as The Talk. We need The New Talk, this one about gun safety.

Over the years, I’d spent countless hours volunteering in my children’s classrooms. I wanted to be involved in their education and their lives. I’ve worn many hats: homeroom mother, overseer of the student store, student directory designer, and liaison for children with special needs. I was a member of both the PTA and the Booster Club. Randy, my husband, sometimes joked about my level of involvement. Others probably saw my “s’mothering” as helicopter parenting. I didn’t care. I hovered, protecting all of the children, not just my own.

Then came Jon’s eighth-grade year, the same year as the Columbine High School shooting. Panic was everywhere. Schools were scrambling to find ways to make families feel more secure, safer. In Austin, where we lived at the time, I received a phone call from a parent at Westlake High School. Jon, my oldest son, was going there the following year. The woman knew about my other school involvement and that I was about to have a high schooler. She asked if I’d be interested in serving on an advisory council for safety and health.

The first meeting was held in the auditorium. I entered the room late, looking across the sea of chairs and around a space that hosted the school plays, searching for a familiar face, but the seminar was already underway.

I slid into an aisle seat, staring at a spreadsheet beaming from a projector. Parents had already put together a list of potential dangers with possible solutions. There was talk about extra lighting, surveillance cameras, monitored doors, and the current procedure for visitors.

Then came the second list. It was directed at us: parents, students, and educators. The speaker explained that securing the building was the first step, but becoming a proactive community was necessary too. “We need to train and educate,” the committee leader said, “so accidents like Columbine can be reduced. I need your help to get the message out.” Of course, Columbine was not an accident. It was an attack unleashed by desperate and disturbed kids. Kids who had handguns available to them.

That day in that school meeting sent a message I’ve heard many times by now: there will always be bad people and we will never be completely safe. But by learning to create a climate of trust and a plan of action, and by educating our children, we might save lives.

Our family moved to North Carolina before I could see all the changes implemented at Westlake. However, I took those lessons about hardware with me. I enrolled my boys in a very small private Christian school. I thought I had done everything I could do to protect my children.

I really believed I had taught them well, right up to the night of Jon’s death. Having endured my loss and that crippling grief, I don’t want what happened to my family to happen to others. I made a huge mistake. I never thought to engage my children in a conversation about handguns or the negligence of others. Where does the responsibility fall? At our own kitchen tables, but also in schools and churches–the places in which we gather to learn and grow.

As said, we have learned to call such a conversation with our teens The Talk. We talk to them about things as important as unprotected sex, drug use, drinking and driving. But unlike a drunk driver, gun owners are not liable for their machinery. We’re not talking about gun safety. Not yet.

I don’t want other families to experience what happened to mine. I never thought to have the new version of The Talk, the one about handguns, with my sons; I urge other parents to do so now. Tell your kids this: Be careful when you see a gun in the room. Ask if it’s loaded. Don’t pick it up without checking it or, better yet, don’t pick it up at all. Leave if you can’t be sure the room with that gun is a safe room. We teach our children not to get into a car when the driver has been drinking, after all.

I see the ever-growing gun culture as one reason for my oversight. I wasn’t prepared to visualize my son enjoying a night out and ending up in a room with unsecured, loaded guns. That practice is not illegal, but the lack of responsibility is a part of gun ownership in North Carolina, Texas, and nearly everywhere else in the US.

I respect everybody’s right to own a gun in America. I’m a member of the NRA. On the other hand, I don’t understand why our schools and our churches and our communities don’t require us to teach and learn gun safety. It’s as if handguns are being sold everywhere without safeties. There’s nothing that can be built into a gun to make it safer. There’s only us.

Our ownership does not eliminate risky behaviors with handguns; they’re deadly weapons whether or not they are possessed legally. We have hundreds of pages of safety rules for stepladders, I learned. Nobody teaches a stepladder safety class in colleges as part of orientation. The schools don’t teach anything about handguns, either. Nobody has to tell me whether a stepladder or a handgun is more deadly–or which can kill someone with intent, or by accident.

Admitting young adults into a college community on their own for the first time, permitted to own and show off a handgun, or even carry one on campus? That’s something we can all work to change. Not to prohibit ownership, but to demand responsibility, because where the responsibility for Jon’s death lies is unclear. The state thought he was responsible, calling it a suicide. Others ask why that gun was in the room loaded. What they mean to ask is why it was loaded–and why no one took responsibility for that weapon. Some might call that negligence, on the part of the parents of those young adults or the kids themselves.

I still ask myself, during those nights and mornings when I particularly miss Jon, where does the responsibility fall? There are no criminal punishments handed out when someone is negligent with a gun. Jon was guilty of holding a gun. He knew the difference between right and wrong, and he knew that holding any gun towards your head, loaded or not, is profoundly wrong. But we cannot dedicate ourselves to preventing gun accidents if we do not take into account the responsibility of the owner.

Owners must have a role to play in exchange for their ownership rights. In the interest of public health, unsafe ownership should be treated like a DUI, until there’s a fatality. I am not advocating jail for every offense. There are laws in some states that do make gun owners responsible when a child dies. But they apply to children under the age of fourteen, and in most cases the gun belongs to their parent. Most prosecutors will not punish those adults, knowing that as parents they have already suffered enough. And they have. I know.

I want to live in a world of that love, where we can begin to make our communities safer in this era of the private handgun. It seems like the schools–where we teach our kids about the dangers of drugs, risky sex, and drinking–is the first place to start. It feels like our churches–where we gather for learning and to find our faith–is a good place, too. We can demand that, and I wish we would. The best place to have a new version of The Talk, though, is in our own homes, or while we ride with our kids in cars and whenever we have their attention (once we quiet the cell phones).

As I tried to find a moral to my painful lesson, I came upon a story in Cosmopolitan about guns and dating. Cosmomight be one of the last places you’d think to look for gun safety advice. But there it was, a story about a set of questions to ask a date about their gun relationship:

- Do you have a gun?

- How did you get it?

- Why did you get it?

- Where do you keep it?

Jon could have asked those questions on that night I lost him. My hope is that those of us who survive him will ask such questions in his memory. We should be talking about this so we can agree on how to act responsibly. Every young adult living in a world of guns must learn gun safety. Our first target can be talking about it, so that the lessons might come before the tragedy–and not after.